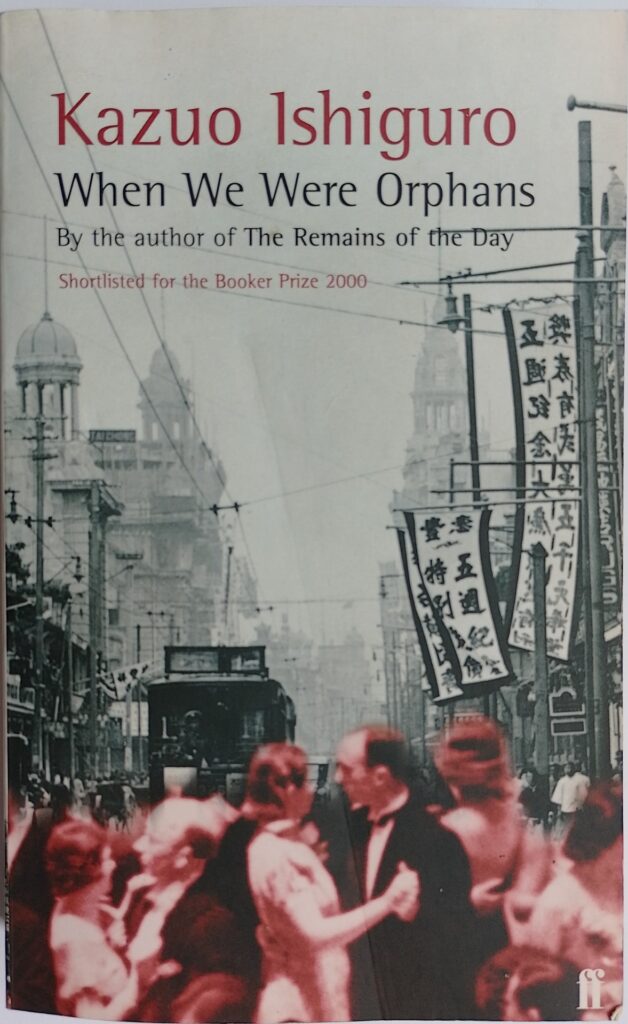

First published 2000. Faber, paperback, 2000, pp 368, c.120,000 words.

This is Ishiguro’s fifth novel, appearing eighteen years after his first. That slow pace is reflected in the quality of the writing and is both an advantage and a disadvantage. Each sentence is beautifully polished, but somehow the overall result is rather dry. This is amplified by his main characters who all seem adrift in this world. This book was short-listed for the 2000 Booker prize.

The protagonist here is rather similar to that in Remains of the Day (Ishiguro’s third, hugely successful novel): Christopher Banks is fastidious, self-obsessed, stiff and deluded, a snob forever name dropping, desperate to avoid disapproval, being laughed at and to be welcomed as an insider. He was born around 1900 and is brought up in the international quarter of Shanghai, where his family live in some style. His father works for a British trading house, and his mother is a campaigner against the opium trade. Banks’ best friend, a Japanese boy named Akira, lives next door. One day Banks’ father disappears and a short while later, so does his mother. Banks is packed off to an aunt and boarding school in England. The book follows his life both in England, where he becomes a successful detective, rather in the Poirot mould (although we have no details of any cases), and then back in Shanghai.

Right at the end Banks muses: ‘But for those like us, our fate is to face the world as orphans, chasing through the long years the shadows of vanished parents.’ And this is what his life has amounted to, that ever-present excuse for failing to engage in the world of emotions and seeing ourselves as we really are. Orphans here remain cowering behind that excuse.

Apart from his mother, there are two significant women in Banks’ life, both of whom are orphans. He remains deluded to the end about them, thinking that he understands their needs and their own follies and completely missing how they relate to him. Perhaps they are the same.

The plot itself is flawed: Banks is supposed to be the great detective and yet fails to follow up important points. The colonel, to who he was entrusted for the voyage to England, tells Banks at a dinner, when Banks is in his early twenties, that ‘There was something fishy about the whole damn business, if you ask me.’ [p31] And yet Banks fails to investigate until much later in his life. I just never believed in Banks as the ‘Great Detective’, expecting at any moment that the idea would be exploded, but it never is. There is very little detection at all, mostly it is about failure to detect. I also had a hard time believing that the expatriate community would all have behaved as they are supposed to have done, and no explanation is given as to why solving some problem in Shanghai will avoid the horrors of looming war.

There is some very high-quality, elegant writing here. Ishiguro is a master at evoking atmosphere. The dangerously unstable world of Shanghai in the first half of the twentieth century is made vivid. The party continues in the international settlement as civil war and foreign invasion takes place all around. The contrast between the settlement and the warren where the Chinese factory workers live is powerfully drawn; the chaos and carnage of street fighting visceral. Despite the plot flaws, the story telling is compelling.

© William John Graham, December 2022