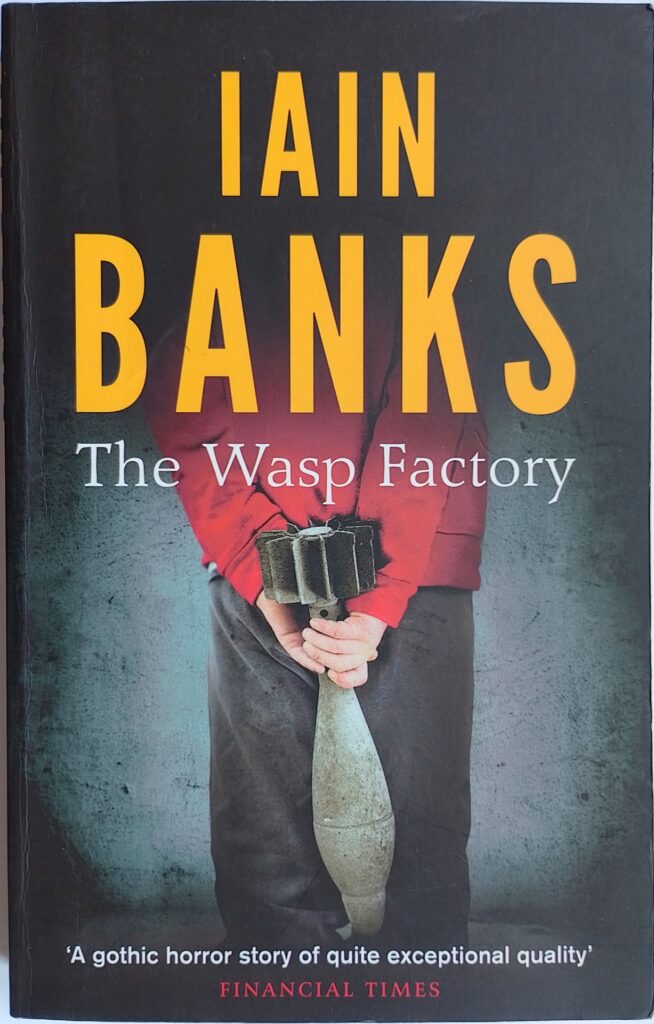

First published 1984. Abacus, paperback, 2013, pp 244, c.75,000 words.

This was Banks’ first published novel, although he had written a number of unpublished science fiction books prior to this. He was then aged thirty and had spent much of the previous decade doing casual jobs which allowed him considerable time for writing.

I had avoided reading this for a long time because the title gave me the creeps. The book lives up to the impression given by the title – although it transpires that the title is not what it might appear to be. Banks has a taste for the macabre which penetrates his science fiction as well as his contemporary novels. Consider Phlebas has a really horrifying passage, and even Look to Windward has its moments of horror.

This might be described as a contemporary gothic-horror story. The main characters are universally evil in some way or other and get up to all sorts of horrible things. Why they are what they are is gradually revealed during the course of the story. The protagonist is Frank, a sixteen-year-old, living with his father in a large house on a small island that is connected to the Scottish mainland by a short bridge. The two await uneasily for the return of Frank’s elder half-brother, Eric. The story is written almost as though it was Frank’s diary, containing occasional mundane trivia.

For once the blurb on the back is accurate. The Irish Times is quoted as saying ‘There’s no denying the bizarre fertility of the author’s imagination: his brilliant dialog, his cruel humour.’ What brought me to finally read this is the quality of Banks’ writing. He evokes a place, a season, a weather pattern with simple economy, effortlessly setting the scene. Small town life in a remote-ish corner of Scotland in the early 1980s seems real. The minor characters are convincingly sketched out as far as is required and uncliched. Most of the horror element in this is vile but minor, and as the critic said, delivered with humour. No animal, insect or bird goes cruelly unpunished. There is, however, at least one scene that is truly stomach turning, so if like me, you are sensitive to this sort of thing, don’t read this unless you have exhausted the rest of the Banks oeuvre. (Pretentious word? Just look at those two SF titles above: both are from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.) Actually Banks is one of the least pretentious of literary writers. He does not use obscure or foreign words or complicated sentence structures. It’s all in good plain, every day, easily readable language, and much the better for it. I was never pulled out of the flow to admire some literary flourish.

Somehow, Banks manages to construct a story within which all the vile activities are realistically consequential from deeds previously done. By the end we understand, even if we cannot forgive, why the characters behave as they do. It is a hugely inventive story and brilliantly written.

© William John Graham, July 2022