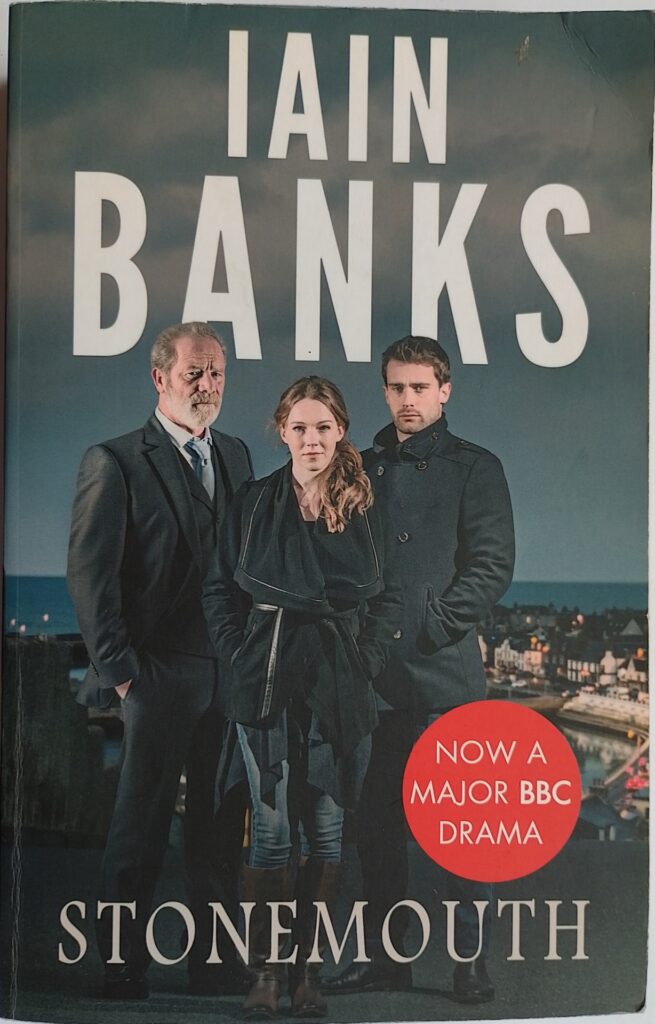

First published 2012. Abacus, paperback, 2015, pp434, c.125,000 words.

There is no doubt that Banks was a great writer. In this book, a pervasive menace hangs over every page. It’s a hugely impressive feat, especially as actual violence is very limited.

A young man is returning to his home town for the funeral of the patriarch of one of the ‘leading families’ of the neighbourhood. Mostly they don’t want him there but are prepared to tolerate his low-profile presence just for the weekend. Five years earlier he had been run out of town for some initially unspecified heinous offence. However, he seems incapable of keeping a low profile, partly because he had been a popular local figure with a large group of school friends who all grew up together, and most of whom are still living in the small town of their birth.

The place is remote and bleak: located on the Scottish North Sea coast somewhere to the north of Aberdeen. The unprepossessing environment is explored and described beautifully, with its mists and rains, its clouds and winds, and its harsh ecology. It’s an important element of the narrative. Banks is superb in giving us the atmosphere of such a place, and in doing so gives us some idea of why it has such a hold on its inhabitants.

Banks uses the present tense for most of the book, which in many less-capable hands can be stagey and uninvolving. Here it is hardly noticeable, and gives an immediacy to the narrative as the protagonist tries to stay out of trouble and work out what really happened in the past, what he means to the people and place now, and what they mean to him. No one’s motivation is entirely clear. Messy humans vacillate and confuse themselves and us with double think and talk: all realistically done.

As this is told from a twenty-five-year-old’s perspective it contains the elements that one might expect from such: an obsession with brands, drugs, alcohol, relationships, material success and social position. Banks was around fifty-eight when he wrote it, so a degree of fantasy is to be expected, and to some extent this is a young man’s fantasy: the protagonist is made out to be a very attractive figure, with all the girls having some degree of desire for him. He is also materially successful, having escaped from his home town, he is now travelling the world as a building lighting designer, and just been promoted to junior partner in his firm (only three years out of art college.) Many of the other characters are cut from larger cloth than one might realistically expect, even if they are all well drawn as identifiable humans.

One might object to the wisdom of the young man returning to the scene of such threat, and then to incapacitate himself regularly with substance abuse, when he might be better served by remaining sharp. Friends can be powerful lures on the road to hell.

There are many flashbacks, some brief and some longer, that fill in how the characters came to view each other as they do. Some of this is quite fleeting, and as a reader, one has to stay alert or miss some thrown off conversational aside that twitches the veil of what is going on. The central relationship is at least partly resolved satisfactorily by the end, but much else is not. There are more loose ends left than in a bowl of spaghetti.

Banks’ writing is his usual fluid perfection. Occasionally he uses local terms, but none are unclear. For example he describes one character as being ‘never the sharpest chiv in the amnesty box’ which I had never heard before but whose meaning is clear [I had to look this up and discovered an ‘amnesty box’ is a place where people may deposit drugs they wish to be rid of, e.g. at an airport. A ‘chiv’ is apparently a home-made knife, as might be found in a prison.] Banks also injects some of his political and religious views into the characters, with material success being a source of suspicion and of failure to live up to youthful idealism. Only at one point did I find this clang a bit loudly.

Overall this is another Banks masterpiece. The sense of place is rock solid, the atmosphere created from the first page is sustained to the last, as are the characterisations. It is highly readable.

© William John Graham, August 2022