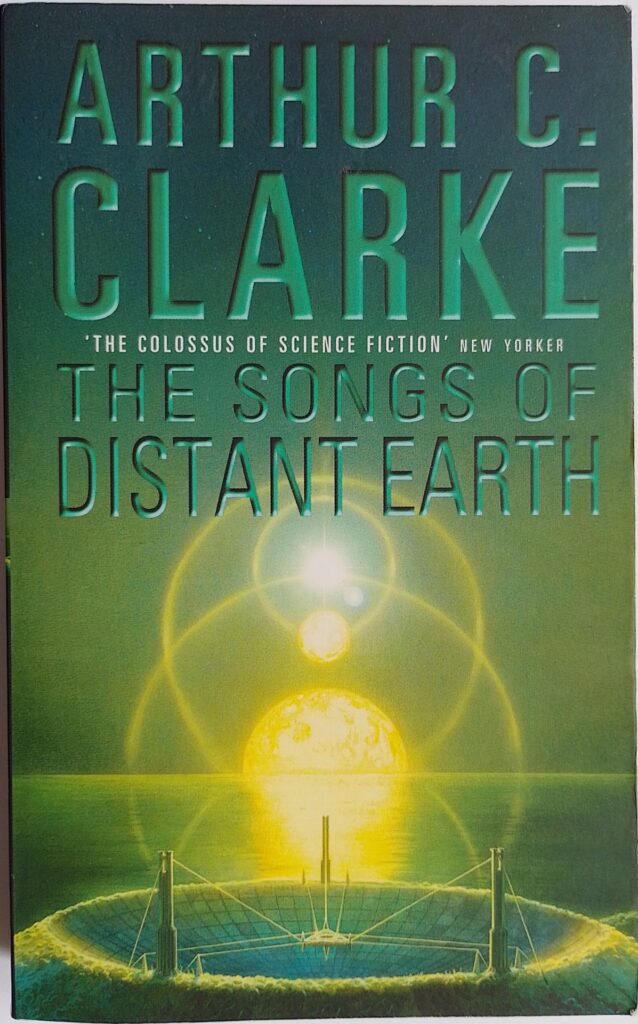

First published 1986. Voyager, paperback, 1998, pp 238, c.75,000 words.

According to a biography of Clarke, one of his jobs was a futurist, and it is in this that he really excels. He clearly had a keen interest in physics and followed and understood the latest developments in that field. In this book, for example, the sun is going unstable as a result of the neutrino deficit problem (a real problem for physicists at the time, but thankfully now explained away), vacuum energy powers his spaceship towards, but not in excess of, the speed of light, a space-elevator is deployed to lift material off a planet, and an electronic archive contains much of the knowledge of Earth in a small device. All the actions in this book are in accordance with the laws of physics as they were understood at the time of writing, even if we don’t have any idea how to realise many of them with today’s engineering. For those interested in how the future might play out, Clarke is essential reading even today.

The story is based on a 12,500-word short story first published in 1958 and is an intrinsically interesting one: the sun will become Nova and destroy the solar system in a thousand years’ time. During that period mankind develops spaceships and sends them off to likely planets around other stars. Some make it and set up viable new settlements. In the last days of Earth a ship leaves using the latest technology and carrying a million people, nearly all of whom are in suspended animation. They aim for a planet which is known to be habitable, and where a settlement was established, but which fell silent several hundred years earlier. It turns out that the settlers are still there and have developed a somewhat utopian community, but hadn’t been bothered to fix their massive antenna to communicate back to Earth. This is a great setup for a clash of cultures.

Unfortunately, Clarke isn’t a great writer of stories. The narrative drive falters as the point of view swings around. Potential plot lines are undeveloped and, as with so much SF from around the 1960s, the characterisations are thin to say the least. I didn’t detect much interiority for any of the main characters, most of whom are stereotypes. Perhaps the only small exception was the spaceship captain who briefly becomes a complex and divided individual. Most of the rest are intellectuals, usually scientists of some sort, honest toilers, or inferior beings. There are no real bad guys here. The ‘love story’ element is unconvincing.

Clarke is rather keener on lecturing us, mostly interestingly, on his take on physics, politics and religion. There are some interesting side stories like the lobsters that are showing signs of intelligence (Did Adrian Tchaikovsky read this before writing Children of Ruin?), the president who is randomly chosen from the citizenry to serve for a year, the discarded lover who accept his fate and then meekly returns when called. All these aspects and many more remain largely unresolved.

Clarke’s wonderfully fertile imagination is well worth the reading. It’s just a pity that it isn’t better packaged into storytelling.

© William John Graham, July 2022