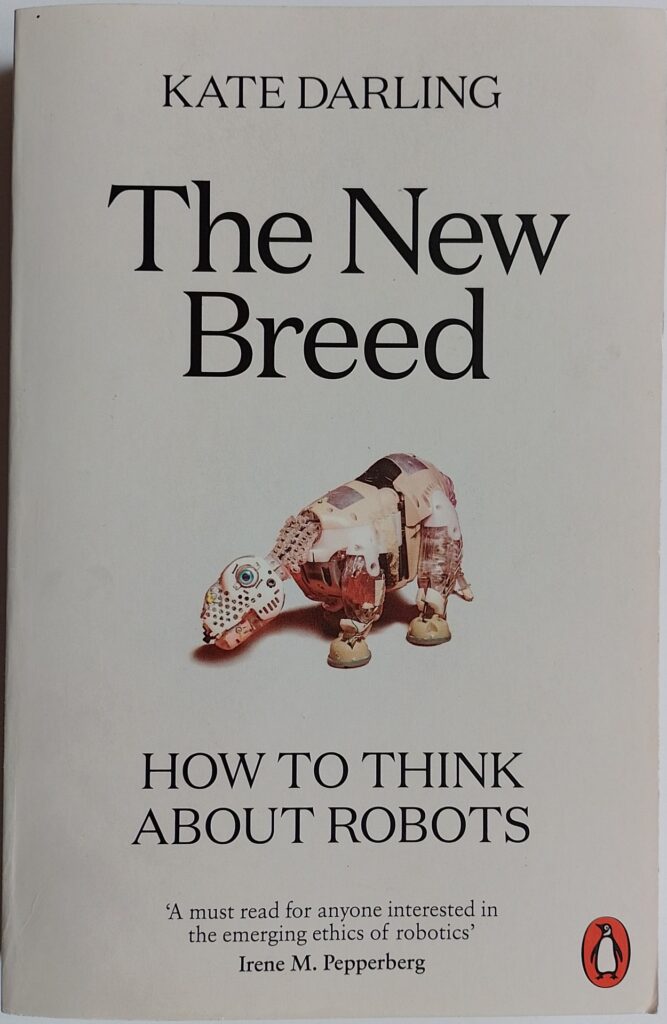

First published 2021. Penguin, paperback, 2022, pp 310 (including 80 pages of notes and index), c.83,000 words (main text).

Kate Darling studied economics and law before teaching and researching the legal and ethical implications of technology. This book distills her thoughts on how robots should be considered in these terms. Her big idea is that they should be treated in the same way as animals are in this context. She presents some good arguments to support her case, but this hardly justifies a whole book. There are numerous anecdotes, often amusing, and side-tracks to fill it out. Don’t expect to learn much about recent advances in robots here.

We are told that the Codes of Eshnunna and Hammurabi, some of the earliest known laws for which we have written evidence, dating from around four thousand years ago, include rules regarding the ownership of animals, such as the penalty if your ox gored someone – you were unpunished if it was the first time it did it, but not if you allowed it to habitually do so. Consequently, today there are large bodies of laws around animal ownership and Darling argues that these could easily be adapted to robots. Robots, like animals, are owned by someone and should not have independent rights. While some argue for animal rights, generally we don’t grant them. There was a period of time in the medieval period when animals could be put on trial, but that practice has disappeared. There are some interesting philosophical discussions here about ‘understanding’ and ‘free will’ for which at some point robots may exceed the capacity of animals, and indeed perhaps even humans, but technology today falls a long way short of that. Disappointingly, this book doesn’t look far forward to possible significant developments in robot autonomy. Perhaps Darling is no futurist and only concerned with the here and now. She does make the point that there is one interesting exception to the notion that only humans have rights and to which law applies and that is corporations. She does not explore how robots might be thought of in that light.

Darling surveys the current field of robots, including industrial, military and domestic assistants as well as autonomous vehicles and human companions – for therapeutic, social and sexual purposes. Indeed, in an opening author’s note she says that there is no agreement on what a robot is and all attempts at definition have fuzzy edges. The only boundary Darling allows herself here is that whatever a robot is, it must have some physical embodiment. She uses the term ‘robot’ because it is evocative and has some scary connotations. There are fears of job displacement, physical danger from industrial or domestic accidents or autonomous weapons, and even, at the extreme, the dystopian idea of the robots taking over from humans and their making us their slaves – we become but animals to the robots. The book raises some important issues such as ‘… there’s a lot of work to do to prevent a future of governments and companies from using social robotics to manipulate people in ways that are against the public interest.’ [p169] But, hey, haven’t they been doing that forever in contexts other than social robotics? Maybe, but robotics provides powerful and insidious new tools.

There are some personal touches in the writing and Darling’s personal views often appear. One can be sure that she is a vegetarian and is upset by some corporate behaviour: ‘the wedding-industrial complex’ for example. A couple of the anecdotes are repeated. Overall her writing is fluid and makes a pleasant read. Each chapter has ‘content warning’ such as ‘animal cruelty’. Is this woke-ism gone mad or intended to be humorous? As an academic, Darling can’t resist sourcing every statement – hence the sixty-two pages of ‘notes’ (= references) and sixteen-page index.

This book raises quite a number of thoughts around what we mean by life, rights, and even the term ‘robots’. Darling raises some a deeply philosophical questions, and – for the current state of the art – makes a convincing case for treating robots like animals for legal and ethical purposes.

© William John Graham, December 2022