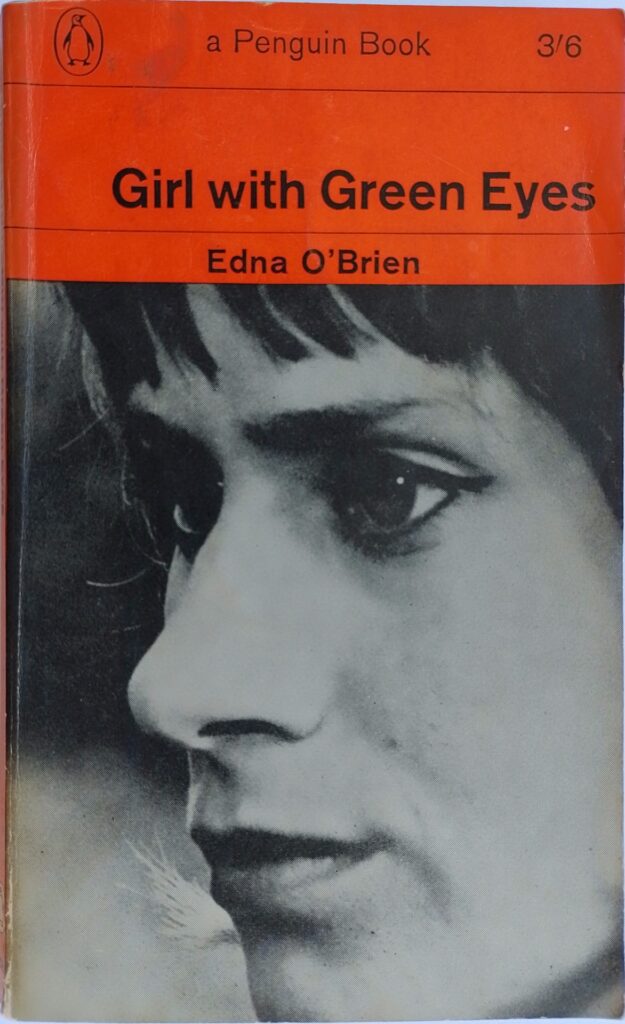

First published 1962. Penguin paperback, 1964, pp 213, c.62,000 words.

This the sequel to O’Brien’s The Country Girls. Its original title was The Lonely Girl, but changed presumably to tie in to the film made from it. It can be read as a stand alone novel, but it is significantly richer for being read in sequence.

Caithleen Brady and her friend Baba have been living in Dublin for a couple of years and are now twenty-one. Caithleen works in a shop, and they share a room in a small boarding house. Both girls spend their free time going out to pubs, dances and the cinema. They are looking for love, but it is hard to find. Eventually Caithleen meets an older man and falls for him. He is well educated, a director and script-writer of documentaries. He owns a nice house in the countryside outside Dublin. Caithleen enjoys kissing him, but gradually wants more.

O’Brien is exceptionally good at drawing young women’s urgent but vague desire for ‘a man’, but also the fear of ‘sin’. This is, after all, Catholic Ireland in the nineteen fifties where, particularly in the countryside, traditional repressive attitudes still hold the population in their thrall. Women are not supposed to desire sex. Men rule their households and not much is done to restrain their drinking and violence towards women. O’Brien is drawing deeply on her own experience of an abusive father and the hypocrisy of the community in which she was brought up.

One fears for Caithleen, and one sees her making the mistakes we all do. Surely Mr. Right will be perfect, but then he is not. Gods have feet of clay. He is mortal too and has his own flaws. The nice men can’t be prised entirely away from their own upbringing and social setting. The conflicts from the age gap in a couple start to emerge. The balance between knowing that one is about to make a mistake and yet being unable to restrain oneself is superbly laid out. The desire is to say the right thing, the smart thing, to be seen as being sophisticated and worldly, and yet somehow we are unable to deliver. We all get tongue-tied when we least want to, say the inappropriate thing, break down in tears when we want to be strong. We are sometimes compassionate even when we know we are being manipulated.

O’Brien’s prose is simple, sometimes appearing naive, matching her protagonist. It is effectively done, drawing us in. Sometimes it seems like a diary, with simple entries recording what happened next, and Caithleen’s thoughts on those events. Some things are left unresolved: the anonymous letter writer is never revealed. One likely suspect turns out to have unexpected strength and loyalty.

This volume doesn’t have the sparkle of childhood that its predecessor had. The tone is more adult, the girls more knowing. It has a more developed human relationship, going from ‘man-mad’ girls to more aware and nuanced desires. It has its flashes of humour, the story bubbles along as it did in the first volume, but this is a more grown-up work, and it lacks the complete novelty of the first. However, the writing is superb, a master-class in efficiency, economy and straight-forward use of language that articulates feeling with great clarity.

© William John Graham, March 2023