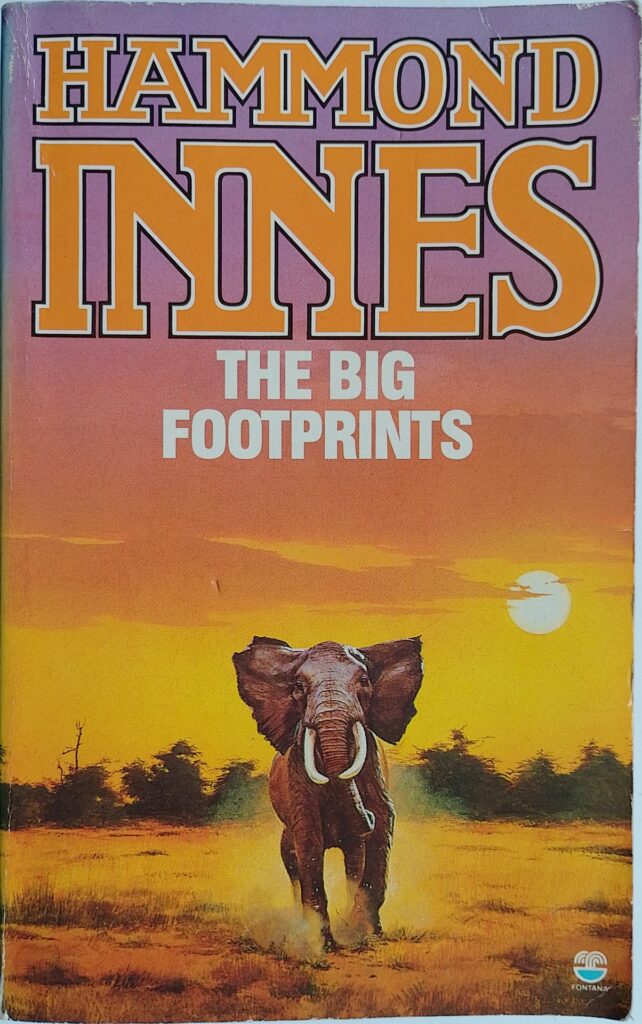

First published 1977. Fontana, paperback, 1988, pp 338, c.110,000 words.

Unusually for Innes this book has no sea voyages, with only one very brief scene involving a raft on a lake. It is a book set in the heart of East Africa – big game country. While the main characters are white, the winds of change are apparent as locals are taking over. This is an unusually tough Innes, with some very gritty scenes of the slaughter of animals, notably elephants. Innes is an able story teller and there is no absolute rights and wrongs here. After a brutal war there is starvation in the land and no tourists. Animals can provide food, at least in the short term, and removing them opens up large tracts of land for agriculture might will feed the rapidly rising population. This is what has happened in Europe, America and elsewhere, so why not in East Africa? Set against those promoting a cull are those who have previously lived by the tourist and ‘white hunter’ trades, and those who dearly love elephants.

The protagonist, Colin Tait, is a British journalist invited to a conference to discuss the issue. Money from overseas to fund the recovery of the country is at stake, so the old white elites still have some power. Tait is an indecisive figure which allows him to equivocate, but rather annoyingly too much. He gets blown around by the politics and a young woman who seems equally divided between the two charismatic old men who used to be partners but are now sworn enemies. Tait never seems to decided anything for himself: events push him in one direction then another. Perhaps that is right for a journalist – just report the facts.

There are some powerfully drawn and visceral scenes of hunting. Innes has clearly visited the places of his story, and as always, fluidly describes the harsh landscape and the ever-changing weather. In an author’s note he says that he met all the well known (white) names in East Africa during his research trip. They include the Adamsons (of ‘Born Free’ fame), the Leakeys (anthropologists and discoverers of early Homo Sapiens), and the Goodalls (of ‘The Gorillas in the Mist’ fame). Innes has taken pains to learn about animal behaviour, particularly that of elephants, although he admits that some of what is described in the book is speculative. Clearly he is very fond of elephants and closes his note with a plea to eschew anything to do with ivory. There is an element of a land in transition and a slight note of elegy. However, the abiding thought that the new future where the local East Africans take charge of their own destiny is the right course.

In a few places the language is obscure to the modern reader: e.g. ‘passepartout’ (adhesive tape), ‘Dannert wire’ (barbed wire), ‘clever as a vervet’ (a type of monkey), and ‘chargul (sic)’ (chagal = a goatskin water bag).

Innes writes fluidly, making for easy reading. His descriptive powers are undiminished and this has a powerful story line. I just wished the protagonist had had a bit more backbone, and I also found some of the hunting scenes hard to read. We, as onlookers if not locals, can only be grateful that, so far, elephants and other wild animals continue to roam over vast tracts of Africa.

© William John Graham, December 2022