First published 1930. The Hogarth Press paperback, 1985, pp 355, c.110,000 words.

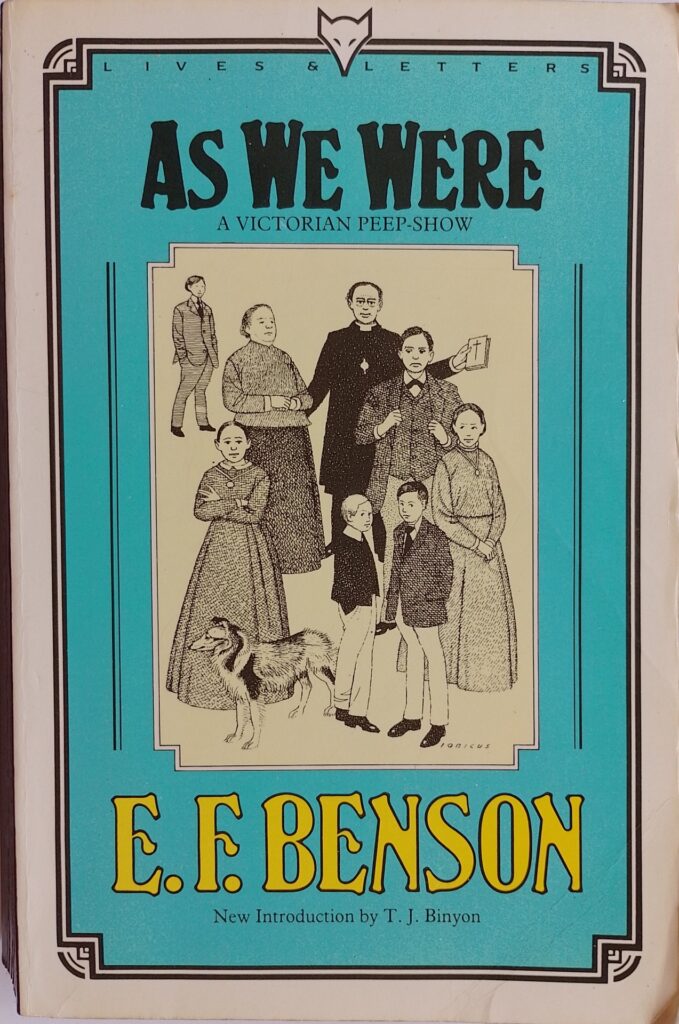

The cover of this edition shows a cartoon of Benson’s parents and siblings, so it was not unreasonable to expect something like a biography of his family, and indeed there is a little here. But the subtitle, ‘A Victorian Peep-Show’, gives a greater hint of what this is about which is a memoir used to highlight how times had changed from the late Victorian period to those when the book was written, i.e. the late 1920s. Although the gap in time since then is greater than the forty odd years Benson is reaching back over, somehow it still seems that there was a greater change in how people thought over that period than in the eighty-odd years since the book was first published. Benson offers only a little explanation for the change: the sway that Victoria herself exerted on society, particularly when contrasted with the very different behaviour of her son, the rapid technological advances in communications and transport, and the volcanic upheaval of the first world war.

The book is not intended to be a scholarly thesis on the changes in society, more a telling of anecdotes that cumulatively give a feel for the late nineteenth century and so point up the differences with the contemporary period of the book. Victoria’s reign was the high-water mark of religious belief and practice in Britain, and Benson’s father became the literal high-priest of the age as Archbishop of Canterbury, a job which probably didn’t suit him, being more political rather than organisational. He was an odd fellow: enamoured of the church and Christianity from an early age and set in marrying his mother from when she was eleven years old. His father was a dynamic man and his mother was apparently an intelligent woman who was intellectually unfulfilled, bearing six children, none of whom married. Benson was either asexual or homosexual: never marrying, buying a house on Capri with his friend Brooks in early 1914 (bad timing that).

I was preparing to hate this book as another fawning, sycophantic tale of hangers on at the tables of dull and bad-mannered aristocrats, rather in the manner of Proust’s later volumes set in the same period. Benson might well have been a bit of a flaneur too, however the twinkle in his eye is present, unlike in that of Proust. Benson is after an amusing story, and we get plenty of those here. There are telling details to some of the most famous incidents of the day, such as the trial of Oscar Wilde and The Tanby-Croft Affair. Benson has a soft spot for Victoria’s eldest son who he credits with far more intelligence than he is generally reconned to have, and putting his reputation as a playboy down to his mother’s treatment of him: giving him absolutely no role in state affairs or consulting him in any way. All that was left for him was a life of pleasure. Victoria otherwise mostly gets a good press here, being credited with an acute sense of a middle-class outlook on life, she was sometimes more astute than many of the politicians of the day on what would pass and her complete absence in public life after the death of Albert eventually ended in strengthening the monarchy.

Oscar Wilde is treated sensibly too. Benson doesn’t credit him with much literary talent but with a supreme gift of the gab, which Wilde foolishly took into the witness box. Wilde’s downfall created his lasting reputation in Benson’s book.

Other artists who Benson knew are also treated with the open eyes of an acute and amused observer. Aubrey Beardsley is credited with being a resounding original genius. Ruskin is credited with some odd views, as are the pre-Raphaelites. These were the circle of artists that Benson knew well, or at least second-hand, at the end of the nineteenth century, and he is able to supply amusing and sometimes illuminating anecdotes : George Meredith, Rosetti, Burn-Jones, Swinburn (who’s creative genius was snuffed out when Watts-Duncan helpfully sort his life out), Edmund Gosse, and Whistler (who sparred successfully with Wilde).

Many of the stories related here do concern aristocrats, mainly women. Benson clearly admired several of them, often for what they had to put up with, and his favourites are usually those who rebel in some way: ‘to be with her was to sit in the sun’ [p310] – how nice. While the names of such people may have faded into the past, these anecdotes of their lives do point up much of the hypocrisy and repression of the late Victorian period which the Edwardian era through the 1920s did much to dispel.

The element that kept me reading is Benson’s fluid facility with finding something amusing in a good story. He wrote many other books acutely observant of the contrast between inner and outer, such as the Mapp and Lucia novels, and he brings that same skill here. Some archaic words are used, ‘epergne’ ‘salicities’, ‘lip-sticking’, and ‘macedoine’ for example, and there are a couple of expressions in Latin and Greek. An informative introduction to this edition by T. J. Binyon (an academic, writer and reviewer) is worth reading.

This book is highly entertaining and in the process one finds Benson’s thesis credible.

Wikipedia biography of Benson: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._F._Benson

Benson enthusiast’s review of the book: http://efbensontheothernovels.blogspot.com/2012/05/as-we-were-victorian-peepshow.html

Others’ reviews of the book (OK, so no one has actually put up a review of this book on ‘Goodreads’ yet): https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/125049646-as-we-were?ref=nav_sb_ss_1_24

© William John Graham, June 2023