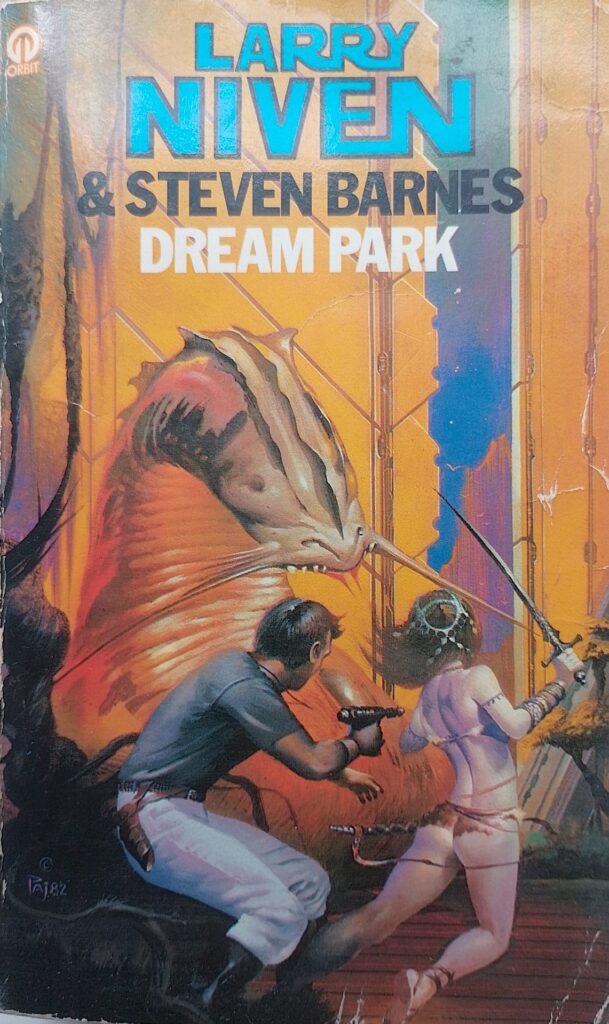

First published 1981. Futura paperback, 1983, pp 430, c.115,000 words.

The opening of this book reminded me of the Jody Foster film Maverick, where a group of gamblers are heading to a big tournament. However this story doesn’t have the sharp wit of that film. Somehow the book doesn’t quite work: the excitement is remote, second-hand. Much of the action concerns a group of people role playing in a game, essentially a fantasy within a fantasy and so the sense of jeopardy is diluted. Death just means being knocked out of the game. There is some attempt to mitigate this failing by setting up a grudge between the person running the game and the lead player, but it doesn’t seem all that consequential; the two don’t come across as real enemies off the field of play; more like old tennis pals trying to outwit each other. The story briefly catches fire when a security guard (outside the game) is really murdered, and the head of security starts to investigate. But then he too is drawn into the game as a substitute player, and the ‘who done it?’ element gets lost in the game play foreground.

That is not to say there isn’t some great invention. In the early 1980s, when this was presumably written, computer games where still relatively primitive. Here, the ‘Dream Park’ of the title is a Disney-World on steroids, a Dungeons and Dragons theme park, where gamers can live inside a game with lifelike monsters generated by holograms. The players feel the atmosphere of the invented world they are playing in, they get exhausted climbing, hiking and fighting. It can be baking hot or freezing. Each player has some kind of magic power that they can deploy to help them fight or evade the monsters and traps. The game is set in New Guinea, and knowledge of local customs and country is helpful. The gamers win by freeing a trapped damsel in distress, collecting buried treasure and finally escaping. The game lasts four days, with breaks for rest.

The players are caricatures: the tough-guy leader, the beautiful women, the older couple, the teenage boy, a disabled woman, etc. None have much depth. There is an awareness that game playing is essentially a trivial exercise, an avoidance of real life. Perhaps this is realistic: some do make a good living as game designers and players that others will pay to watch and emulate. Today the computer games industry is a large one.

While the gaming may still be futuristic, some of the background is retro: a man wears a jacket [p31] and there is a secretarial pool somewhere [p145]. The sexual politics of the 1970s seems to prevail, with women coming off worse as usual. The cover of my edition no doubt accurately targets the expected reader demographic.

The writing is straightforward and would make for easy reading except for the naming of the many characters, most of whom have three names which are used at random: a family name, a given name, and a game-role name. Fortunately, a cast list is placed at the beginning of the book, but it doesn’t help the flow to have to keep referring to it. There are a couple of good lines: ‘The Dream Park Sheraton was decorated in Twenty-First Century Mundane’ [p41] and ‘…a face incredibly aged and weathered. Only the eyes seemed truly alive: chips of diamond stuck in a withered black apple.’ [p190].

One strictly for gamer fans perhaps.

Wikipedia biography of Niven: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_Niven

Wikipedia biography of Barnes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Barnes

Wikipedia summary of the book: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dream_Park

Others’ reviews of the book: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/357922.Dream_Park?ref=nav_sb_ss_1_10

© William John Graham, May 2024