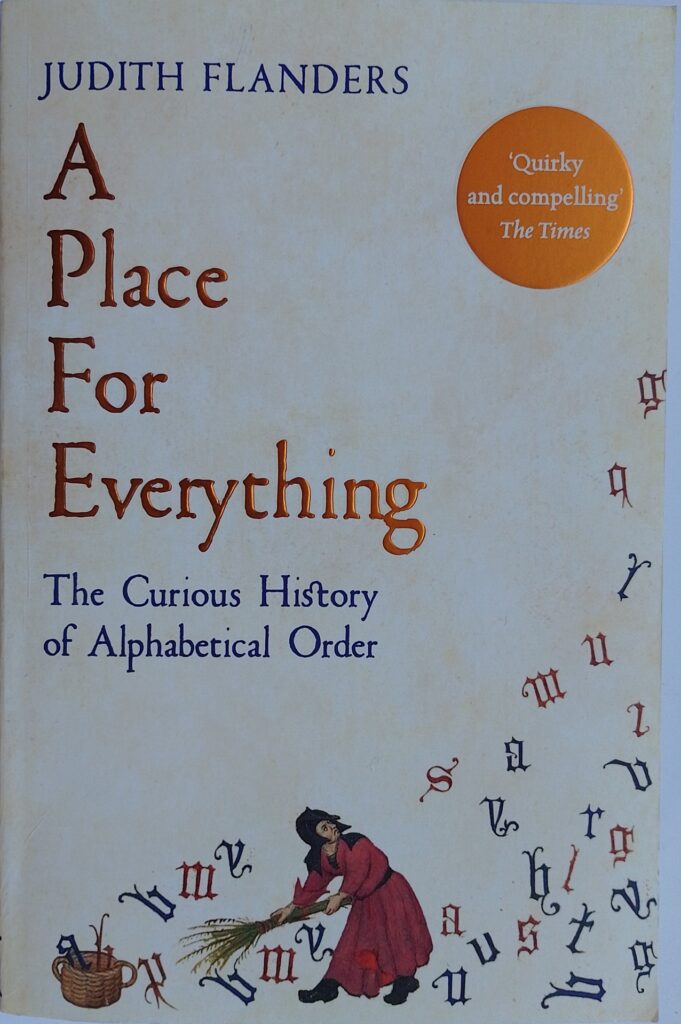

First published 2020. Picador paperback, 2021, pp 376, c.80,000 words (main text).

It had never struck me before that the word ‘alphabet’ is simply a contraction of the names of the first two letters of the ancient Greek alphabet. This is about the only point that Flanders doesn’t make in this book on the subject of sorting and retrieval of information. What a truly odd book this is.

As Flanders points out, when books were few and kept by monasteries, popes and a few immensely wealthy individuals there was no need to consider how to order them. It was easy enough to pick out the required volume from memory of its location and look. It wasn’t until paper and printing arrived in Europe (and this book is almost exclusively concerned with Europe) that having some sort of system was required to aid the retrieval of a particular item. Paper was so much cheaper than velum and printing so much cheaper than hand copying that there was a massive increase in book production.

There had been some need for making retrieval easy for documents prior to paper and printing, most notably for laws, decrees and commercial documents, although it seems justice relied rather more on word than document in earlier times. Many archives were simply filed in chronological order. Early libraries might be sorted by hierarchy: Bibles, the works of the ‘Church Fathers’, lesser works, or God, kings, nobles, etc. in descending order. No one knows how the library at Alexandria – possibly the largest collection of classical texts ever assembled – was organised: scrolls use up far more space than books.

Another important need for information retrieval during the medieval period was picking out passages from the Bible and the Church Fathers for the purpose of sermonising and religious argument. ‘Concordances’ were compiled, but how were they to be ordered?

There is something very nerdy, but strangely compelling, about this deep dive into the world of ordering and information retrieval. However, here there are precious few amusing anecdotes and the medieval section gets rather bogged down in all the various and ever-changing systems used to organise. This is a flaw that other academic historians have fallen into when writing ‘popular’ works: they are terrified of leaving anything out in case one of their academic colleagues reads it and says ‘ah, but in St. Remotus monastery on the island of Scarpa in 1351 they organised their library by…’ The general reader doesn’t care but wants the nuggets of gold and the big sweep. Similarly, including a timeline (pp 5), a bibliography (pp 22), notes (pp 37), an index (pp 12), contents list (pp 2), list of illustrations (pp 2), acknowledgements (pp 2), and a preface (pp 12) seems like overkill, or even padding, to the general reader. One might say everything has been ordered so that it is easy to find. Sadly that is not true of the main text which is divided into ten chapters in roughly chronological order. Each is given a letter title: A is for Antiquity, etc., although the tenth chapter is not J but Y for Y2K, which has nothing to do with the millennium bug, but tries to bring the story up-to-date by considering computerised systems of classification and search. Search systems might have been of great interest, but currently perhaps more the province of the computer systems and software designer than the historian. Chronological order is not followed strictly either: ‘Then in 1286 came…’ [p115] when earlier there had been discussion of the 15th century.

There are some humorous asides; one I particularly liked was a list of causes of death with its unexpected last catch-all category [p145]. One might quibble with a few of the statements such as that the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I invented government documents in the late fifteenth century when one only has to consider the Norman invasion of Britain in 1066: the Normans found it relatively easy to control and tax the country because of the excellent systems already established by their Anglo-Saxon predecessors, and they added to it with the ultimate government document: The Doomsday Book. Of course Flanders writes ‘One historian suggests that it was in the reign of…’ [p166] rather than claiming it as a fact about Maximilian.

A fascinating source of information for researchers that I had not thought about before is the study of pictures from the past. Occasionally a sitter was placed amongst their work and Flanders has picked some examples and explains what is going on: in backgrounds are documents sorted using strings, sacks or pigeonholes, or even, using that still present prospective newspaper-article phrase: being spiked.

The book contains some fine illustrations of illuminate medieval manuscripts with their interlining glosses and surrounding commentaries. I was rusty on some of the printing and editing terminology used here: ‘glosses’, ‘florilegia’, ‘running heads’, etc.

Flanders always translates non-English words – good: I hate it when an author assumes my Latin or German is good as theirs.

The Guardian’s comment quoted on the back says ‘… it reveals what a weird, unlikely creation the alphabet is.’ I took it from that that the book would delve into the origins of the alphabet itself, those twenty-six or so odd symbols that we use to construct our (Indo-European) languages. She only very briefly touches on their origins in Egyptian hieroglyphs. I was sorry there wasn’t rather more on this aspect, which does seem rather fundamental to the subject. Flanders is here focused on the parts of the world where alphabetic languages are used. She mentions in passing that there are other places which use ideographic writing, most notably in Asia. It might have interesting to compare how the Chinese, for example, historically classified and retrieved information, particularly as they had paper and printing long before Europeans.

While Flanders’ thesis might be the rise of the alphabet as a neutral means of classification that has come to dominate all others, she acknowledges that it is rarely the top level: look in any bookshop and you will find that books are ordered first by genre and only then by alphabetic order of the surname of the author.

Overall I found this a mildly fascinating and generally well written read. Perhaps I ended up having read too much about the subject.