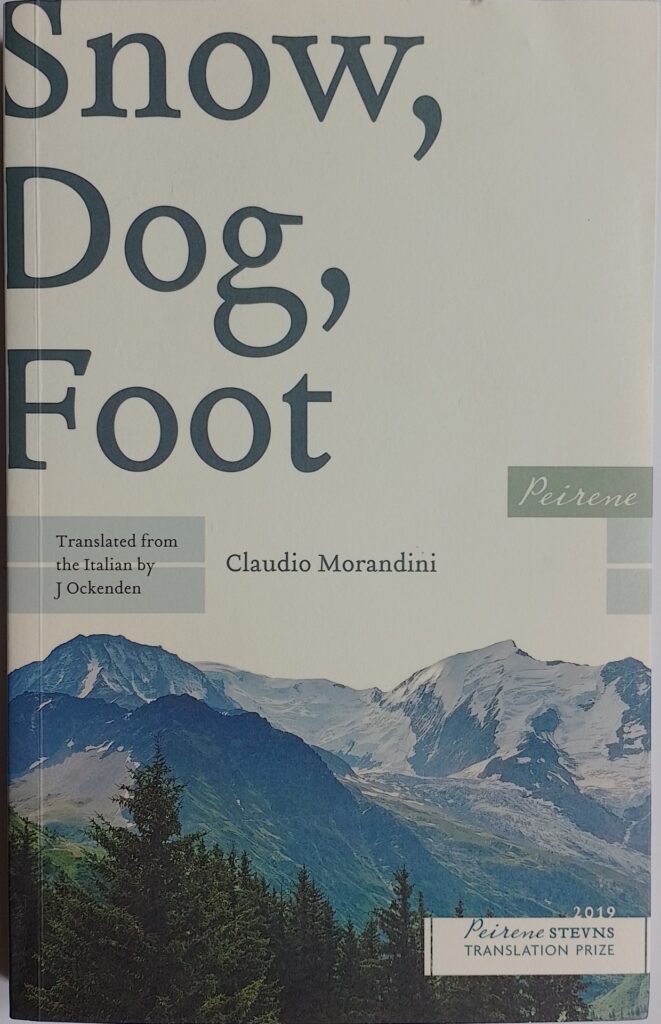

First published 2015. Peirene paperback, 2019, translated by J Ockenden, pp 124, c. 33,000 words.

This is a fine example of how few words can be perfect. One might feel short-changed by such a slim volume being sold by Peirene for 20% over the odds for a ‘normal’ length paperback, but in this case the quality of the work justifies the price.

Adelmo Farandola is an old man living on his own, high up in the mountains. He is the sort of person most of us would try to avoid – and he would like it that way. He is smelly, taciturn, abrupt if not downright rude, unkept, angry, uncaring, indifferent. We are inside his head, in the present tense, were we gradually come to learn who he is. The landscape is similar: harsh, unyielding, cracked, broken, unstable, intensely cold or burnt by the sun. It is desiccated, where the leaves dry on the trees before they have time to fall. The winds are relentless, snow piles up to cover the house in winter, avalanches frequently crash down from the mountains, bringing death. There is a brief summer when life bursts forth, but it is inhabited by spiders and grasshoppers, and it brings unwelcome hikers.

A dog arrives from somewhere and attaches itself to the man. Like him, it has nowhere better to go. The dog gives us its point of view and has conversations with the man. Everything here has a voice: mountains, snow, ice, even cold, hunger and sleep. All have their moods and tones. There is nothing twee about these voices and conversations: this is a harsh place and they come from inside the mind of a man driven into himself. Yet there is considerable humour in this uncompromising viewpoint.

The man is becoming detached from the real world, presumably in the early stages of dementia. He is forgetful of what happened yesterday, but as we gradually learn, he remembers some justifying episodes from his past. The few people that he encounters try to help, but he rejects them. Although he tolerates the dog, and in some way needs the dog’s companionship, he threatens to eat it if his winter food supply runs out before the thaw. When spring does come, a foot is exposed, and this leads to the final unravelling.

This book was a best seller in Italy, garnering literary prizes. The translation into English is excellent: hugely atmospheric and fluid. I did balk slightly at the phrase: ‘shut it’, used twice, because it immediately reminded me of the catch phrase of John Thaw’s Regan from ‘The Sweeny’: that 1970’s TV police drama. Ockenden won the Peirene Stevns Translation Prize by submitting a translation of the first chapter of the book.

A member of staff in my local bookshop actively sold this to me. It was an excellent recommendation.

© William John Graham, February 2023