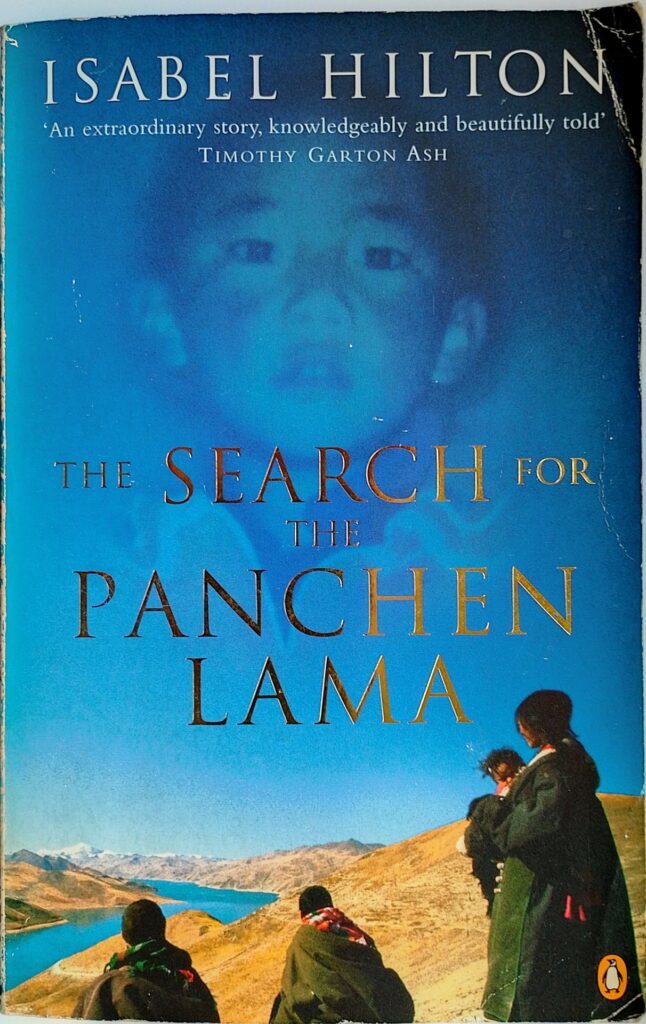

First published 1999. Penguin paperback, 2000, pp 336, c. 120,000 words + maps, index, notes and photographs.

This is a real-world tragedy, the story of a unique culture, centuries in the making, slowly fractured by great-power rivalry and then utterly dismantled by fanaticism and political greed.

Hilton studied Chinese at university up to post-graduate level and then became a journalist. She followed the story of the search for the 11th Panchen Lama since meeting the Dalia Lama for a documentary in 1994.

The Panchen Lama is the second highest rank in Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama. There are a considerable number of other lamas, each of which is held to be the reincarnation of the previous holder of the title. The search for the new incarnation begins soon after the death of the previous one, and is usually found as a baby born shortly after the death, although there seems to be considerable flexibility. The search is supposed to be conducted by senior monks under the guidance of special signs and visions. The baby can be born into very modest circumstances and is identified by specific bodily marks, miraculous events surrounding him and his ability to identify objects associated with the previous incarnation. When possible the Dalai Lama guides the identification of the next incarnation of the Panchen Lama (and the reverse also happens) and has ultimate authority to recognise the true next incarnation.

Tibet is a country surrounded by high mountains and deserts, offering little in the way of material opportunities, and therefor historically has been relatively isolated and secure. Buddhism has been practised there since perhaps as early as the 3rd c., and been the formal religion since the 7th c. when the Tibetan empire included a broad swath of territory, particularly to the south and east of the mountain plateau. Buddhism developed into a pervasive and dominating aspect of the society, rather similar to Christianity in medieval Europe, with wealth and education dominated by monasteries. The Dalai Lama held considerable sway over secular society as well as providing spiritual leadership. Hilton describes him as a ‘theocratic king’ [p3]. However his powers were limited, depending on the cooperation of other monasteries as well as his own in Lhasa. Tibetan Buddhism is divided between sects, and rather akin to modern corporations, are rivals for power and influence.

The Qing empire invaded Tibet in the eighteenth century, effectively taking control and absorbing the eastern parts of Tibet into its own neighbouring provinces. In the nineteenth century Tibet was surrounded by three great powers: Tsarist Russia to the north, British controlled India to the south and the Qing empire in China to the east. Each of these was wary of the risk of the others seizing control of Tibet. As the Qing empire began to fall apart at the end of the nineteenth century, Tibet regained its independence, but it was never strong enough to withstand the predations of its neighbours. The British lost interest in expanding its colonial empire and Russia lost a war to the Japanese. That left the emerging Chinese nationalists, and later communists, to reassert control over Tibet. Once Mao was firmly in charge of China, he pushed his communist agenda into Tibet with disastrous consequences for the prevailing Buddhist culture. The Dalai Lama was seen as a focus for Tibetan nationalism and was eventually forced to flee to India. The tenth Panchen Lama was much more accommodating and provided a degree of legitimacy to the communist takeover. However, even he found the starvation of the Tibetan people during the ‘Great Leap Forward’ hard to take (it had never happened before) and was for ever after treated with suspicion by Mao and his successors.

In 1994, five years after the tenth Panchen Lama’s death, Hilton arranged to visit the Dalai Lama for a documentary film she was making and from then on became absorbed by the process of selecting the Panchen’s next incarnation. She describes the hopes and fears of the various parties vying to influence or direct the process. It was a tragedy played out over many years, involving many people and much political machination. Ultimately there was only going to be one winner: the one holding the guns.

Hilton interleaves her own visits to China, Tibet and India over the period as she followed the unfolding drama, even playing a minor, ultimately futile, part at one point. She fills in the background story of Tibet in the twentieth century, particularly as it relates to the role of the Panchen Lama along the way. Her writing is fluid, easily readable, and not overburdened with extraneous detail. There is a lot of human interest in the story, how each player, like all of us, is flawed, makes errors of judgment, occasionally sticks up for what is right, even to our personal detriment. Only the stony hearted could fail to be moved by this sad tale.

© William John Graham, February 2023