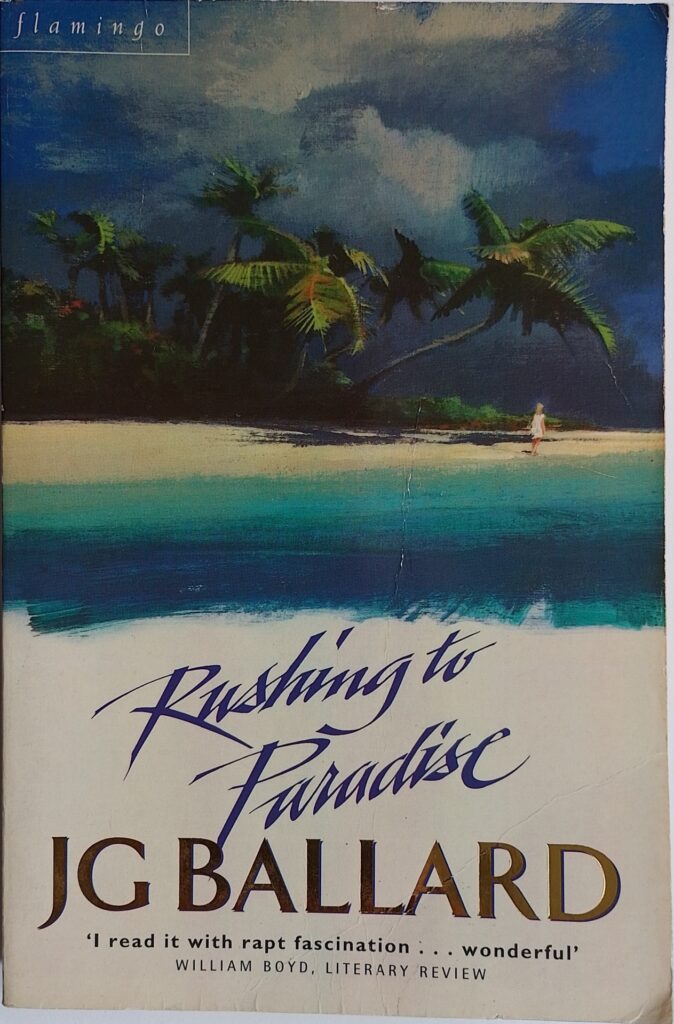

First published 1994. Flamingo paperback, 1995, pp 239, c. 80,000 words.

A group of environmentalists sets off to a small pacific island to stop a French nuclear test and to save the albatrosses there. They are led by Dr Barbara, a charismatic woman, and the story is largely told from the point of view of one of her acolytes, Neil, a teenage boy. Each character has their own reasons for following Dr Barbara and these are convincingly portrayed.

Ballard’s style is somewhat journalistic, often delivered in short, fact driven sentences, but the cumulative effect is mesmerising, reflecting the leadership of the campaign. The result is powerful and dream-like, and the borders between doing good and doing evil fluid. The descent into madness is well graded (a familiar Ballard theme). There are hints of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, the self-immolation of fanatical cults such as that at Jonestown in 1978 and of the complicity of those around any charismatic leader in what follows, even to the participants’ own destruction.

There are hints dropped along the way of where the trail is leading: that fatal ‘trust me’ [p61]. ‘The need for enemies…’ [p135] and the cult-like nature of the events depicted is made clear: ‘like any fundamentalist sect.’ [p138]. However, Ballard is not making the case for established authority. Criticism is levelled at the French authorities as well as by-standers who do nothing. Sympathy is evoked for the environmental aims of the group. Ballard is saying that all human action has mixed motives and mixed results – good and bad are not the preserve of the few enlightened.

By half-way through, the book has become a bit of a who-done-it. There is the obvious suspect, but then as we are so used to being mis-directed in mystery-thrillers, the reader starts to wonder if someone else is carrying out the dirty deeds, even if they are doing so while under the thrall of the leader: I was only carrying out orders…

There are some humorous little touches along the way as the islanders start to eat the rare creatures they have been sent to preserve: ‘… fortunately the world supply of rare and endangered mammals seemed inexhaustible.’ [p181]

The book draws us along in its decent into hell. It is very well written, making it easy and compelling reading, with some nicely turned phrasing. It retains Ballard’s characteristic rather detached style.

© William John Graham, February 2023