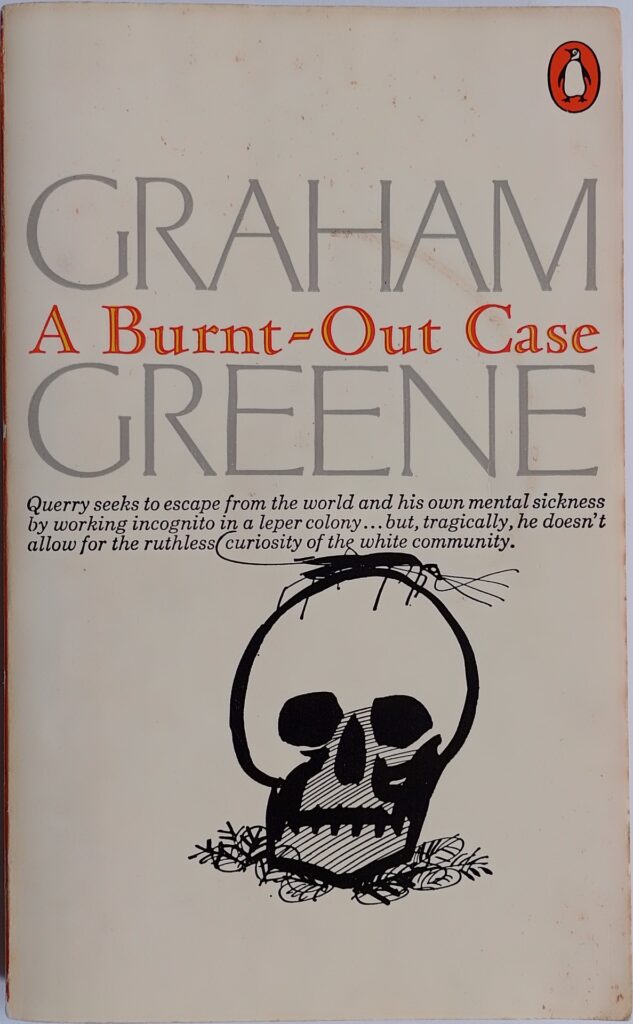

First published 1960. Penguin, paperback, 1971, pp 208, c. 66,000 words.

This is one of Greene’s ‘Catholic novels’ where characters discuss and are driven by, at least in part, their faith or lack of it. By the end, Greene seems to be saying that the degree of faith someone has is not correlated to their human decency. There are good and bad Catholics, just as there are good and bad non-believers.

The primary setting here is the same as Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness, the upper reaches of the river Congo where ‘civilisation’ is thin at best and disease rampant. Greene’s chosen setting is a leprosy colony, set up and run by Catholic priests, but where the doctor is an atheist. Into this world comes Querry, a once famous architect, best known for his Catholic churches and cathedrals. But now he is brunt-out, having lost his vocation, his faith and his desire. He seeks solace in anonymity. Querry seems to be an Ayn Randian architect of monumental ego who despises those who paid for his work and those who have to use the buildings for any changes they might make.

Africa may be the setting of the story but Africans feature hardly at all. Only one African rates a name, and that an absurd one given him by the priests; and he is a servant and former leper, now burnt-out, i.e. non-infectious, but desperately disfigured by the disease. All the other characters are white colonials (and nearly all men): priests, other do-gooders, business people, journalists, or administrators. Only one woman gets a significant role and she is treated as a child by the men, and consequently acts like one: ‘She thinks the truth is anything that will protect her.’ [p204]

Greene occasionally turns a vibrant phrase: ‘… suffering is something that will always be provided when it is required.’ [p17], or ‘The pouches under is eyes were like purses that contained the smuggled memories of a disappointed life.’ [p33] or ‘but he could hear nothing except the rattle of crickets and the swelling diapason of the frogs.’ [p55]. Sometimes one feels that Greene is reaching too hard – does the sound of crickets really ‘rattle’? Is the use of ‘revenant’ right to describe an absent door in an unfinished building? [p132] Does a DDT truck really ‘cannon’ [p64] Such overcooked metaphors can set up a dissonance and remove the reader from the flow. Similarly when a novelist mentions a writer in a story it causes us to suspend our disbelief (it didn’t work for Shakespeare either.) Greene seems to be trying to get in ahead of his critics when he writes ‘Was this the reward perhaps which came sometimes to the writer? “I have told all: you can hang me now.”’ [p163]

Enjoyment of this book will rest on the reader’s appetite for explorations of faith. ‘You’re too troubled by your lack of faith,’ Querry is told by one of the priests. Other than that, Greene is a first-class writer, creating powerful atmosphere, strong, troubled characters and a driving plot. It sits as an interesting, but lesser, companion piece to Conrad’s work in this forbidding setting.

© William John Graham, February 2023