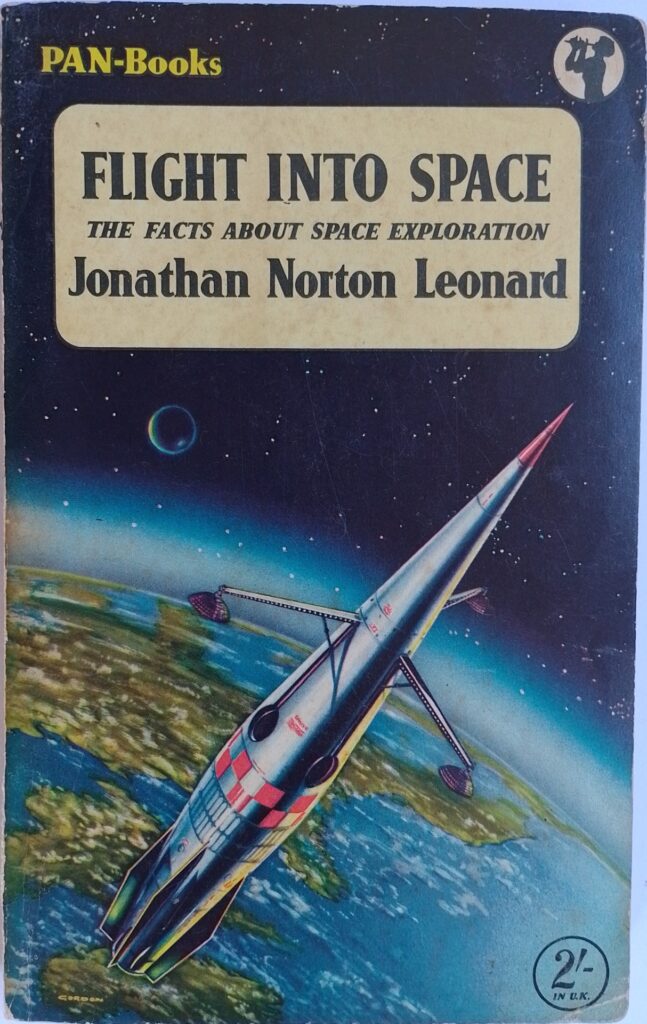

First published 1953. Pan, paperback, 1957, pp 192, c.75,000 words.

This book provides a snapshot of how the West viewed the possibility of space travel in the early 1950s. Leonard had been Science Editor of Time magazine for ten years at the time this was written, and he had excellent access in the USA to both military, as far as it was allowed, and civilian research into space, space vehicles and human space flight. He witnessed the testing of missiles at the US military’s White Sands Proving Ground.

As far as human space flight was concerned, there were two camps in the U.S. at the time. The optimists were led by Werner von Braun, who had been the head of Germany’s V2 rocket development and been taken to the USA after WW2. He was clearly a very charismatic man, and happy to speak publicly to promote his ideas. He advocated a crash programme to develop a set of space stations that would provide take off points for exploring the Solar System. Also, to gain access to the massive military budget, the stations would be used to monitor military activity in the Soviet Union and as platforms for an overwhelming strike capability, allowing the USA to dominate the world militarily. The opposing camp did not have a charismatic leader, and most of their people were bound by secrecy because they were part of the military establishment. They favoured a more cautious, step-by-step, approach to building a nuclear weapon missile capability. They thought von Braun’s proposal a big distraction and would divert huge resources into a project that would inevitably fail.

Much was unknown about space and space travel in 1953. Leonard goes through half a dozen or so, such as heat control in spaceships (either too hot in the glare of the sun or too cold when in shadow), similarly light intensity contrasts, the danger from cosmic rays and space particles, the design of a viable spacesuit and the problems of surviving in a zero-gravity environment. Leonard is aware that the military men may have be feeding him a pessimistic line because they wanted to put the Soviet Union off developing their own space capability.

At that time, there was very limited knowledge of the Moon and the planets. No one knew if there was life on Mars, for example. Leonard writes ‘Nearly all astronomers admit that Mars has some form of vegetation on it.’ It was extremely difficult to get a clear picture of the planet’s surface because even the biggest telescope, the 5m Mount Palomar, could not get a good image because of the instability caused by the Earth’s atmosphere.

Leonard draws out how life has evolved from the sea to the land, which he suggests is as big a jump as from Earth to space. He writes convincingly of the inevitability of that move being made. He makes the point that evolution has been driven by increasing social complexity, the move from single-cell life to the highly complex, multi-cellular life that exists today, where the single cell has given up all its individuality to become part of a greater whole. He saw the increasingly large social structures that were evident in his day, for example in corporations and cities, where individuals perform highly specialised tasks, of value only when combined with many others. He projects that to suggest, in the distant future, a new type of life will emerge that is far more complex than existing forms. Aliens may have already done that and be unrecognisable and unfathomable social structures, far beyond our imagination (I thought of Solaris by Stanislaw Lem and Starmaker by Olaf Stapledon when I read this.)

One can see what a shock the launch by the Soviets of Sputnik in 1957 must have been to America. Prior to this it was safely assumed in America that the U.S. had a commanding lead in space. One can also see the seeds of the Apollo programme in von Braun’s already formed ideas.

The book is a fascinating historic document as well as a good primer on the hazards of space travel. It is well written, without jargon or mathematical equations, and yet does not shy away from explaining some difficult topics.

© William John Graham, July 2022